|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

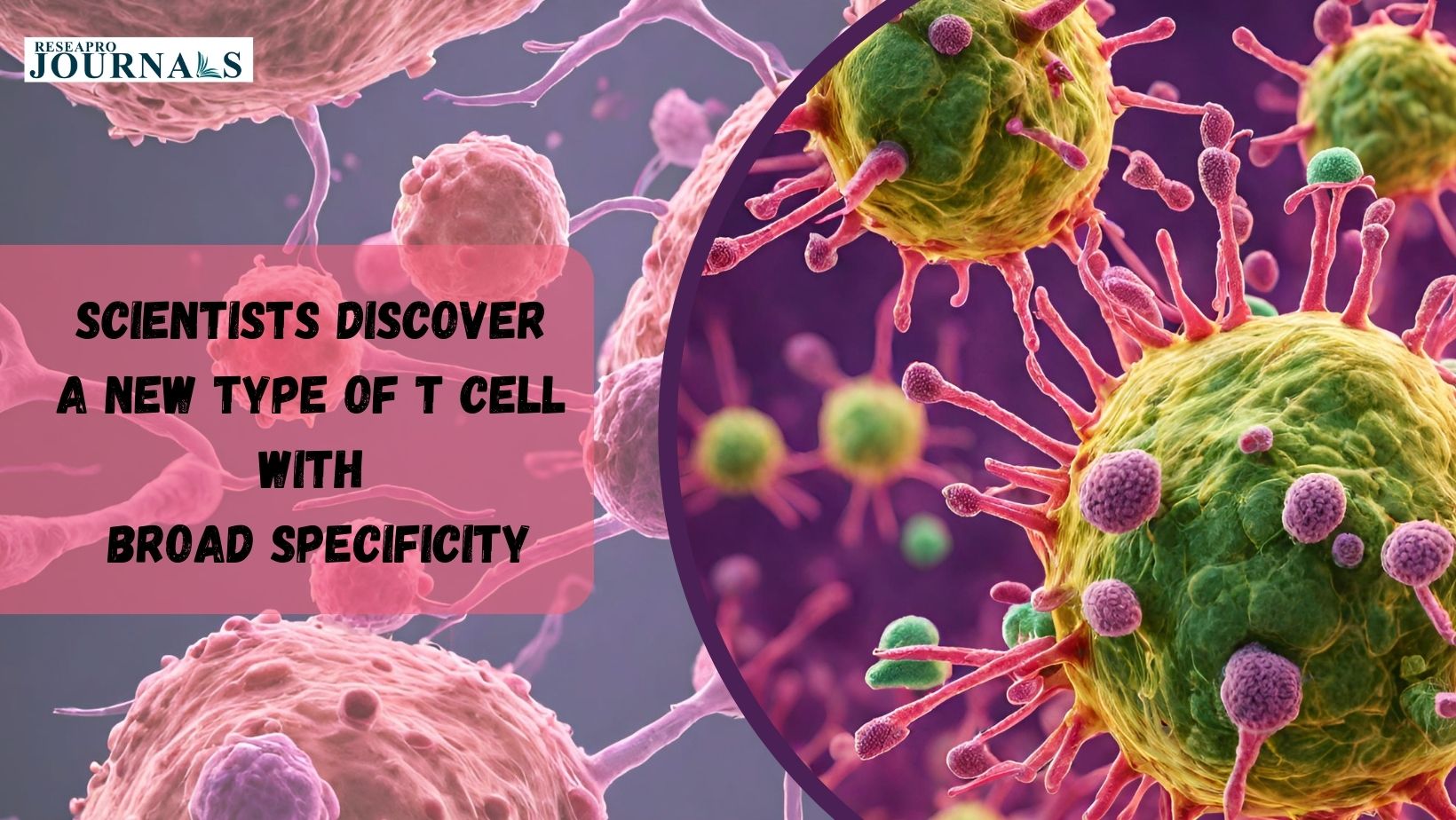

Scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) are investigating a talented type of T cell called mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells. These cells are unique in that they can recognize a wide range of markers, including those shared between humans and even between species. This makes them potentially useful for treating infectious diseases and improving cancer immunotherapies. The new study, published in Science Immunology, sheds light on the genes and nutrients that give MAIT cells their fighting power. The findings are an important step toward one day harnessing these cells to treat infectious diseases and improve cancer immunotherapies. MAIT cells are much faster than typical T cells because they can respond to more generic markers of infection, rather than hunting for very specific tissue-type markers. For MAIT cells, a red flag is a red flag, no matter who is waving it. The new study shows that MAIT cells don’t just recognize a range of markers within one person. Instead, these odd T cells can “see” markers shared between humans — and even between species. Scientists call these kinds of shared markers “conserved.” There has been no reason for the markers to change over the eons, so they remain the same across related species. This broad specificity makes MAIT cells similar to the immune system’s first-responder cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, which make up the “innate” immune system. The researchers hope that their findings will lead to the development of new therapies that can harness the power of MAIT cells to fight disease.